Ambarabà Ciccì Coccò

Italian Nursery Rhyme

Original Lyrics

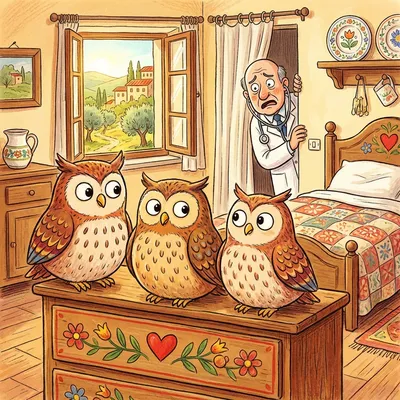

Tre civette sul comò

Che facevano l'amore

Con la figlia del dottore;

Il dottore si ammalò

Ambarabà ciccì coccò!

English Translation

Three owls on the dresser

Who made love

With the doctor's daughter;

The doctor fell ill

Ambarabà ciccì coccò!

Translation Notes

Vocabulary

Ambarabà ciccì coccò — nonsense words; possibly derived from corrupted ancient Latin

tre — three (number)

civette — owls (literally); also "flirts" or "seductive women" (figurative meaning since Middle Ages) - Singular: civetta = little owl / flirtatious woman

sul — on the (contraction of su + il) - Su = on - Il = the (masculine)

comò — dresser, chest of drawers (from French commode, entered Italian ~1700s)

che — who, that (relative pronoun)

facevano — they made, they did (imperfect tense, third person plural of fare, "to do/make")

l'amore — love (preceded by definite article l') - Fare l'amore = to make love, to court, to have romantic relations

con — with (preposition)

la figlia — the daughter

del — of the (contraction of di + il)

dottore — doctor

il dottore — the doctor

si ammalò — he fell ill, he became sick - Reflexive verb from ammalarsi (to fall ill, to become sick) - Passato remoto (simple past) tense, suggesting a completed action in the past

Grammar Notes

Contractions of Prepositions + Articles: Italian contracts prepositions with definite articles: - Sul = su (on) + il (the masculine) = on the - Del = di (of) + il (the masculine) = of the - Con la = with the (feminine); note con doesn't contract with la

Relative Pronoun "Che": Che (who, that, which) introduces relative clauses: "tre civette... che facevano" (three owls... who made).

Imperfect Tense "Facevano": The imperfect tense (facevano) describes ongoing or habitual past actions: "they were making" or "they used to make." This contrasts with the simple past (si ammalò) which describes a completed action.

Reflexive Verb "Ammalarsi": Italian uses reflexive verbs for many actions affecting oneself: - Ammalare = to make sick (transitive) - Ammalarsi = to become sick, to fall ill (reflexive) - Si ammalò = he became sick (himself)

Passato Remoto "Si ammalò": This is the passato remoto (simple past/preterite), used for completed actions in the distant past or in formal/literary contexts. In modern spoken Italian, passato prossimo (si è ammalato) would be more common, but rhymes often preserve older verb forms.

Definite Article with Body Parts/Possessions: Italian uses the definite article where English uses possessive adjectives: "la figlia del dottore" (the doctor's daughter) rather than "his daughter."

"Fare l'amore": This idiomatic expression literally means "to make the love" but translates as "to make love" or "to court." The use of the definite article (l') is required in Italian.

Circular Structure: The rhyme's return to "Ambarabà ciccòcoccò" at the end creates a perfect circle, allowing children to repeat it indefinitely while counting. This circular structure is characteristic of counting-out rhymes across many cultures, ensuring no predetermined endpoint that could advantage or disadvantage particular children.

History and Meaning

"Ambarabà Ciccì Coccò" is one of Italy's most famous traditional nursery rhymes, a filastrocca (counting-out rhyme) that has been used by generations of Italian children to select who's "it" in playground games. The rhyme is immediately recognizable for its mysterious, nonsensical opening words and its surreal imagery of three owls on a dresser, followed by a bizarre narrative involving a doctor's daughter and the doctor falling ill. While the rhyme appears to be pure playful nonsense designed for its musical rhythm and counting function—similar to the English "Eeny, meeny, miny, moe"—scholars have uncovered fascinating layers of meaning. Linguist Vermondo Brugnatelli proposed in 2003 that the opening phrase may derive from ancient Latin, and literary giant Umberto Eco dedicated an entire semiotic essay to analyzing the rhyme as if it were an artifact of an alien culture. The rhyme's perfect circular structure, catchy rhythm, and mysterious quality have ensured its survival through oral tradition for centuries, possibly extending back to ancient Rome.

Origins and Etymology

The precise origin of "Ambarabà Ciccì Coccò" remains uncertain, but linguistic and cultural evidence suggests it may be several centuries old, with possible roots extending back to ancient Rome. The rhyme belongs to the genre of filastrocche—Italian counting-out rhymes used by children in games to determine who will take a particular role or go first.

The most intriguing aspect is the seemingly nonsensical opening: "Ambarabà ciccì coccò." For generations, Italian children simply accepted these as meaningless syllables chosen for their rhythmic and musical qualities. However, in a 2003 linguistic study, scholar Vermondo Brugnatelli proposed a fascinating etymology: the phrase may derive from the ancient Latin "HANC PARA AB HAC QUIDQUID QUODQUOD," which roughly translates to "prepare this (hand) from this other (which is counting)" or "repair this (hand) from that other (that is counting)."

If Brugnatelli's hypothesis is correct, this would directly connect the rhyme to its historical use in counting games, where children would point to each participant in turn, moving from "this hand" to "that hand" while counting. The Latin phrase would have been progressively corrupted through centuries of oral transmission by children who didn't understand Latin, eventually becoming the musical nonsense syllables we know today. This linguistic transformation—from meaningful Latin to pure sound—would demonstrate how children's oral traditions preserve rhythms and phonetic patterns even while losing original semantic content.

The presence of "comò" (dresser/chest of drawers) in the rhyme provides a terminus post quem (earliest possible date): the word "comò" entered Italian from French around the 1700s, suggesting that the current version of the rhyme, at least the "tre civette sul comò" portion, likely dates to no earlier than the 18th century, though earlier versions may have existed with different imagery.

The earliest known literary attestation of the rhyme with its current words dates to 1972, though oral tradition clearly predates this by many generations.

Meaning & Interpretation

While "Ambarabà Ciccì Coccò" is primarily functional—designed for counting games rather than storytelling —its seemingly absurd narrative has attracted scholarly interpretation:

"Ambarabà ciccì coccò" Possibly corrupted ancient Latin for counting preparation (see Origins above); functions as musical nonsense syllables

"Tre civette sul comò" (Three owls on the dresser)

This surreal image introduces the rhyme's bizarre world. The word "civetta" in Italian has a double meaning: it literally means "owl" (specifically a little owl), but since the Middle Ages, it has also been used figuratively to describe a seduct ive or coquettish woman. Some interpretations suggest the "three owls" might actually represent three perfume bottles on a dresser, subtly alluding to femininity, vanity, and seduction within what appears to be a children's rhyme—a coded adult joke hidden in plain sight.

Why owls rather than other animals? Owls have long been associated with both wisdom and mischief in European folklore, making them perfect protagonists for a whimsical rhyme.

"Che facevano l'amore / Con la figlia del dottore" (Who made love / With the doctor's daughter)

This provocative line has sparked debate. A recent online rumor suggested the original text contained "che facevano timore alla figlia del dottore" (who frightened the doctor's daughter) instead of "facevano l'amore" (made love). However, this has been thoroughly debunked: the earliest literary attestation (1972) already uses "l'amore," and the "timore" version appeared only as an unsubstantiated Wikipedia edit in 2019.

In the context of children's rhymes, "facevano l'amore" should likely be understood more innocently than its literal translation suggests—perhaps meaning "courted" or "flirted with" rather than explicit sexual activity. The double meaning of "civette" as both owls and seductive women enriches this interpretation.

"Il dottore si ammalò" (The doctor fell ill)

The narrative reaches its conclusion: the doctor—presumably the father—fell ill. Is this from stress over his daughter's romantic entanglements? From the shock of discovering owls (or seductive women) in his house? From jealousy? The rhyme doesn't say, leaving the cause-and-effect relationship delightfully ambiguous.

The circular structure: The rhyme then loops back to "Ambarabà ciccì coccò," creating an infinite cycle perfect for counting games.

Umberto Eco's Analysis

The famous Italian writer and semiotician Umberto Eco (1932-2016) dedicated a paradoxical semiotic essay to "AmbarabàCiccì Coccò" in his 1992 work "Il secondo diario minimo" (The Second Minimal Diary). Eco's essay analyzed the rhyme as if it were an expression of an alien culture whose language and customs we must decode.

Eco highlighted the rhyme's progression from: 1. Obscure, invented words ("Ambarabà ciccì coccò") that resist interpretation 2. Surreal imagery (three owls on furniture) that defies everyday logic 3. Narrative sequence (owls make love with doctor's daughter, doctor falls ill) that, while seemingly illogical, follows a recognizable cause-and-effect pattern

Eco's analysis demonstrated how the rhyme creates its own internal logic and world, one that children accept without question. The juxtaposition of nonsense

, surrealism, and narrative structure makes the rhyme both meaningless (as pure counting device) and rich with interpretive possibility (as cultural artifact).

Cultural Significance

"Ambarabà Ciccì Coccò" has been passed down through oral tradition for generations, creating powerful continuity in Italian childhood culture. Its enduring popularity stems from several factors:

Perfect Counting Structure: The rhyme's rhythm and syllable pattern make it ideal for pointing to each child in turn, with the circular structure allowing indefinite repetition until someone is selected.

Memorability: The nonsense syllables, unusual imagery, and narrative absurdity make the rhyme extremely memorable—precisely because it doesn't make conventional sense.

Oral Tradition: Like "Eeny, meeny, miny, moe" in English or "Am, stram, gram" in French, the rhyme has survived entirely through children teaching it to other children, demonstrating the power of oral transmission.

Cultural Touchstone: Virtually every Italian knows this rhyme, creating shared cultural memory across regions and generations.

Scholarly Interest: The rhyme has attracted serious academic attention (Brugnatelli's linguistic analysis, Eco's semiotic essay), elevating a children's game into an object of scholarly inquiry.

Variations

While the most common version uses "tre civette" (three owls), regional and personal variations exist:

- "Tre galline sul comò" (three hens on the dresser)

- "Tre scimmiette sul comò" (three little monkeys on the dresser)

These variations maintain the rhyme's structure while substituting different animals, though the owl version remains dominant throughout Italy.